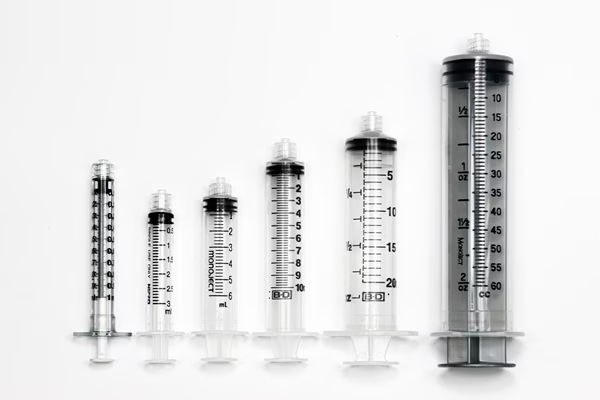

Syringes: The Anesthesiologist's Precision Instruments

In the high-stakes environment of anesthesia, the humble syringe is far more than a simple fluid container. It is a precision instrument, an extension of the anesthesiologist's hand, and a critical component of safe drug delivery. The choice of syringe size is a deliberate clinical decision, guided by principles of accuracy, safety, and the specific task at hand. This write-up details the various syringe sizes and their indispensable roles in anesthesia practice.

Guiding Principles: Why Syringe Size Matters

Before examining specific sizes, it's crucial to understand the logic that governs their selection:

Dosing Precision: Smaller syringes have finer calibrations, allowing for more accurate measurement of potent, low-volume drugs. A 0.1 mL error in a 1 mL syringe is a 10% dosing error, whereas the same error in a 10 mL syringe is only 1%. For powerful medications like fentanyl or epinephrine, this precision is non-negotiable.

Injection Pressure: Physics dictates that for a given force, a smaller-diameter syringe barrel generates higher pressure than a larger one. This is critical when performing nerve blocks; a small syringe allows the anesthesiologist to feel subtle changes in resistance, while a large syringe is used for high-volume, lower-pressure injections.

Volume and Viscosity: Larger syringes are necessary for drawing up and administering larger volumes of less concentrated drugs or more viscous solutions (like propofol).

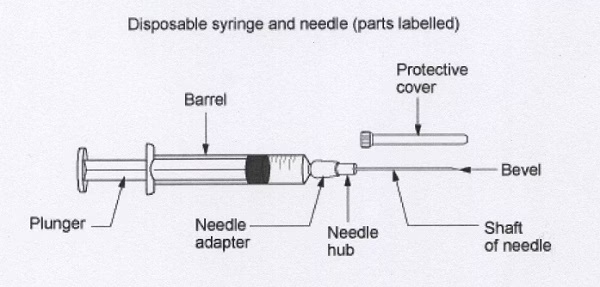

Safety and Connection: The Luer-lock connection is the standard for almost all IV applications to prevent accidental disconnection, especially under pressure.

A Tour of the Anesthesia Cart: Syringes and Their Specific Uses

1 mL (Tuberculin) Syringe

- The Role: The instrument of ultimate precision.

- Primary Uses:

- Pediatric and Neonatal Dosing: Essential for accurately administering tiny drug doses to infants.

- Potent Opioids: Drawing up and administering concentrated fentanyl, sufentanil, or remifentanil.

- Vasopressors: For preparing and administering small, carefully titrated doses of phenylephrine or epinephrine.

- Test Doses: Administering a small test dose for epidural or spinal anesthesia to rule out intravascular or intrathecal placement.

3 mL Syringe

- The Role: The undisputed workhorse of the anesthesia workspace.

- Primary Uses:

- Induction Agents: Drawing up and administering most induction agents (e.g., etomidate, ketamine).

- Muscle Relaxants: The standard size for administering rocuronium, vecuronium, and succinylcholine.

- Common IV Drugs: The go-to for anti-emetics (ondansetron), steroids (dexamethasone), antibiotics, and moderate doses of opioids (morphine, hydromorphone).

- IV Line Access: Flushing peripheral IVs and drawing blood samples from arterial or central lines.

5 mL Syringe

- The Role: The versatile all-rounder.

- Primary Uses:

- Larger Drug Volumes: Useful when a drug comes in a larger vial or when multiple drugs are mixed in one syringe.

- Local Anesthesia: Drawing up local anesthetic for peripheral IV insertion or small field blocks.

- Aspiration: Provides better negative pressure than a 3 mL for aspirating from a central line to confirm blood return.

10 mL Syringe

- The Role: The bridge between small-volume drugs and large-volume tasks.

- Primary Uses:

- Propofol: Commonly used to draw up propofol from its 20 mL ampule.

- Flushing: The standard size for flushing arterial lines and central venous catheters.

- Regional Anesthesia: Often used for injecting local anesthetic for intermediate-sized nerve blocks.

20 mL Syringe

- The Role: The specialist for aspiration and regional anesthesia.

- Primary Uses:

- Loss of Resistance (LOR): The definitive syringe for identifying the epidural space. The air- or saline-filled barrel allows the anesthesiologist to feel the "give" as the needle passes the ligamentum flavum.

- Large Volume Nerve Blocks: Injecting the larger volumes of local anesthetic required for blocks like a supraclavicular brachial plexus block or a femoral nerve block.

- Aspiration of Blood: Efficiently clearing blood from a catheter or for rapid blood sampling.

50 mL / 60 mL Syringe

- The Role: The fluid management tool.

- Primary Uses:

- Line Flushing: Thoroughly flushing and clearing large-bore central lines, rapid infusion catheters, and introducer sheaths.

- Preparing Infusions: Accurately adding a drug to a 50 mL or 100 mL bag of IV fluid to create a medication infusion (e.g., a norepinephrine drip).

- Bolus Fluid Administration: Manually delivering a rapid fluid bolus in situations of hypotension or hemorrhage.

Beyond the Barrel: Luer-Lock vs. Luer-Slip

- Luer-Lock: Features a threaded tip that twists onto a needle or catheter, creating a secure, leak-proof connection. This is the standard of care for all IV drug administration, arterial line management, and any procedure where disconnection could be catastrophic.

- Luer-Slip: Features a friction-fit tip that simply pushes on. Its primary use in anesthesia is for drawing up medication from a glass ampule. The twisting motion required for a Luer-lock can place torque on the glass neck, increasing the risk of it breaking. Once the drug is drawn up, it is often expelled into a Luer-lock syringe for administration.

Conclusion

The selection of a syringe is a fundamental, yet often overlooked, aspect of anesthetic practice. From the 1 mL syringe delivering a life-saving micro-dose to the 20 mL syringe identifying the epidural space, each size has a distinct purpose rooted in the principles of physics and pharmacology. Mastery of these tools—understanding which to use, when, and why—is a subtle but vital skill that underpins the precision, safety, and efficacy that define modern anesthesia.