Ambulatory and Portable Anesthesia: The Evolving Landscape of Anesthesia Care Outside the Main Operating Room

The practice of anesthesia has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past few decades, moving beyond the confines of the traditional hospital operating room (OR). This shift has been driven by technological advancements, economic pressures, and a patient-centric focus on convenience and efficiency. At the forefront of this evolution are two closely related yet distinct subspecialties: Ambulatory Anesthesia and Portable Anesthesia. While they often share principles and techniques, they differ in their scope, setting, and logistical challenges.

Ambulatory Anesthesia (Same-Day Surgery)

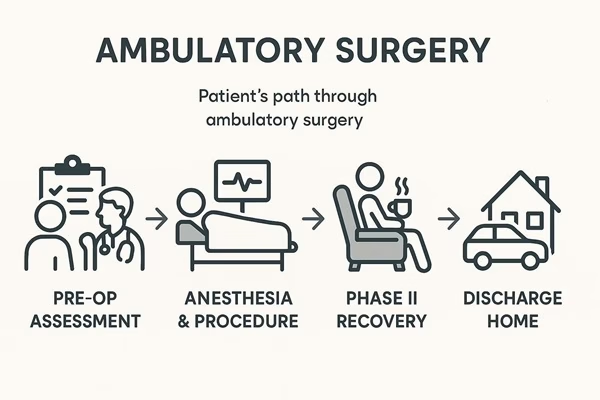

Ambulatory anesthesia, also known as outpatient or same-day surgery anesthesia, is a specialized service model designed for patients undergoing surgical, diagnostic, or therapeutic procedures who are expected to go home on the same day.

The Core Philosophy

The primary goal of ambulatory anesthesia is to provide excellent operating conditions for the surgeon while ensuring the patient's comfort and safety, all while facilitating a rapid, smooth, and complication-free recovery. The entire process—from pre-operative assessment to post-anesthesia discharge—is streamlined for efficiency.

Key Principles:

- Rapid Recovery: Anesthetic techniques are chosen specifically for their quick onset and, more importantly, their rapid offset.

- Minimizing Side Effects: A major focus is placed on preventing common postoperative issues like Post-Operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV), significant pain, and prolonged drowsiness.

- Fast-Track Protocols: Patients are often moved directly from the operating table to a phase II recovery area (or "recliner chair") to bypass the more intensive phase I recovery, accelerating the discharge process.

Common Anesthetic Techniques

- Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC): This is not "just sedation." It involves the administration of anxiolytics, analgesics, and sedatives by an anesthesia provider who continuously monitors the patient's vital signs and physiological status. The patient remains responsive but is in a state of reduced awareness and discomfort. It's common for cataract surgery, minor orthopedic procedures, and interventional radiology.

- General Anesthesia (GA): Full unconsciousness is induced. In the ambulatory setting, GA relies heavily on modern, short-acting agents.

- Induction: Almost always with Propofol, prized for its rapid onset and quick recovery, and its anti-emetic properties.

- Maintenance: Either with volatile anesthetics like Sevoflurane or Desflurane (which have low blood-gas solubility, allowing for quick wake-up) or a total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) technique using a Propofol infusion.

- Regional Anesthesia: This involves numbing a specific region of the body, such as a limb or the lower half of the body.

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks: A single injection or a continuous catheter is placed near a nerve cluster to numb a specific area (e.g., a femoral nerve block for knee surgery). This provides excellent, long-lasting pain relief with minimal systemic side effects.

- Spinal or Epidural Anesthesia: Commonly used for lower body procedures like hernia repairs or urological surgeries.

Portable Anesthesia (Anesthesia on the Move)

Portable anesthesia refers to the delivery of anesthesia care in locations outside of a standard OR, often using specialized, compact, and mobile equipment. This is a logistical approach to providing care, and it is essential for the growing field of procedures performed in "Offsite" or "Out-of-Operating Room" (OOR) locations.

The Scope and Settings

The demand for portable anesthesia has exploded as complex procedures have migrated to non-traditional settings. These locations include:

- Radiology Suites: For MRI and CT scans in children, uncooperative adults, or painful procedures like biopsies and ablations.

- Endoscopy Suites: For upper endoscopies (EGD) and colonoscopies.

- Gastroenterology Clinics: Similar to endoscopy suites but often in a freestanding clinic.

- Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) Rooms: Requires a precise anesthetic technique to manage the physiological response to the treatment.

- Dental Offices: For extensive oral surgery in patients with special needs or high anxiety.

- Cardiovascular Labs: For procedures like pacemaker insertion or electrophysiology studies.

- Field Hospitals and Disaster Zones: Providing surgical care in austere environments.

Key Challenges and Considerations

Providing anesthesia in these locations presents unique challenges that demand a high level of vigilance and adaptability.

- Unfamiliar Environment: The anesthesia provider may not be familiar with the layout, equipment, or staff of the location.

- Resource Limitations: Access to emergency equipment, drugs, and personnel (e.g., a rapid response team) may be delayed or limited.

- Equipment Constraints: Standard OR anesthesia machines are too large and cumbersome. Portable anesthesia workstations must be compact, reliable, and often battery-powered.

- Environmental Hazards: MRI suites pose unique dangers (projectile risk from ferromagnetic objects, interference with monitoring equipment). Radiation exposure in interventional radiology is another concern.

- Logistics: Transporting all necessary equipment and medications to the site and ensuring everything is in working order requires meticulous planning.

Next: The Core Components of Modern Ambulatory & Portable Anesthesia →

Page 1 of 2

The Core Components of Modern Ambulatory & Portable Anesthesia

The success of both ambulatory and portable anesthesia hinges on specific pharmacological choices, specialized equipment, and stringent safety protocols.

Pharmacology: The "Fast-In, Fast-Out" Drug Arsenal

The choice of drugs is critical to achieving a rapid recovery.

- Hypnotics (for sleep):

- Propofol: The cornerstone of both ambulatory and portable anesthesia. Its rapid metabolism allows for quick awakening and a low incidence of nausea.

- Analgesics (for pain):

- Remifentanil: An ultra-short-acting opioid metabolized by blood enzymes, allowing for its effect to wear off in minutes, regardless of infusion duration. Ideal for painful but brief procedures.

- Fentanyl: A short-acting synthetic opioid commonly used for its quick onset.

- Ketamine (in low doses): Provides analgesia and can reduce opioid requirements without significant respiratory depression.

- Muscle Relaxants:

- Rocuronium + Sugammadex: This combination is a game-changer. Rocuronium provides reliable muscle relaxation, and Sugammadex can reverse its effects completely and rapidly in minutes, eliminating the long wait times associated with older reversal agents.

- Anti-Emetics (for nausea prevention):

- Ondansetron, Dexamethasone, and Aprepitant are routinely administered to prevent PONV, a leading cause of delayed discharge and hospital admission.

Equipment: The Anesthesia "Go-Kit"

Portable anesthesia requires a self-contained, robust set of equipment.

- Portable Anesthesia Workstation/Ventilator: A compact machine that integrates a ventilator, gas delivery system, and monitoring capabilities. It must be battery-operated and durable.

- Comprehensive Monitoring: ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) standard monitoring is non-negotiable and includes:

- ECG (Heart rhythm)

- NIBP (Non-invasive blood pressure)

- SpO2 (Pulse oximetry)

- EtCO2 (End-tidal carbon dioxide) - Essential for confirming breathing and detecting problems early.

- Temperature and anesthetic gas concentration.

- Airway Equipment: A full range of equipment for managing a difficult airway, including various laryngoscope blades, supraglottic airways (like LMA), and a video laryngoscope.

- Emergency Drugs & Equipment: A readily accessible "crash cart" or kit containing emergency drugs (e.g., epinephrine, atropine, anti-arrhythmics), a defibrillator, and emergency airway tools.

The Future of Ambulatory and Portable Anesthesia

The field continues to evolve rapidly. Future trends include:

- Even Shorter-Acting Drugs: Development of new agents with more predictable and rapid clearance profiles.

- Advanced Technology: Wireless, wearable monitors; smaller, smarter ventilators; and the integration of ultrasound for both vascular access and nerve blocks.

- Telemedicine: Remote consultation and mentoring for anesthesia providers in rural or remote locations.

- Expanding Scope: More complex surgeries, such as bariatric procedures and certain cancer surgeries, are being safely performed in an ambulatory setting.

Conclusion

Ambulatory and portable anesthesia represent a paradigm shift in surgical and procedural care. They demand a unique blend of clinical expertise, adaptability, and meticulous planning. By leveraging modern pharmacology and technology, anesthesia providers can deliver safe, high-quality care in a wide variety of settings, prioritizing patient comfort and rapid recovery. This subspecialty is no longer a niche practice but a cornerstone of modern healthcare, enabling more patients to receive necessary care with greater convenience and lower cost.

← Back to The Core Philosophy of Ambulatory & Portable Anesthesia